Coin Metrics’ State of the Network: Issue 212

The basics of hash functions and a toy model of Bitcoin Mining

Get the best data-driven crypto insights and analysis every week:

State of the Network Foundations: Hashes

By Alex R. Mead & Kyle Waters

Introduction

In this week’s State of the Network we return with our Foundations series, which presents various “technical” aspects of blockchain technology in an approachable way. In this week’s issue, we turn to the concept of a hash, one of the core cryptographic elements enabling the cryptocurrency space as a whole.

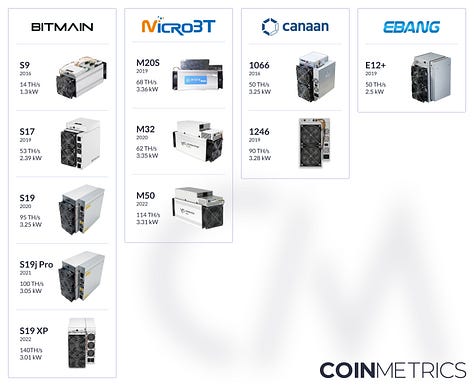

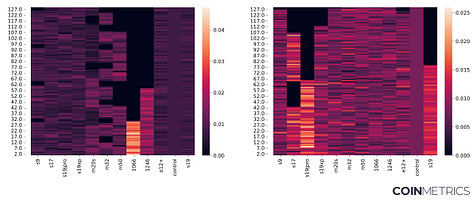

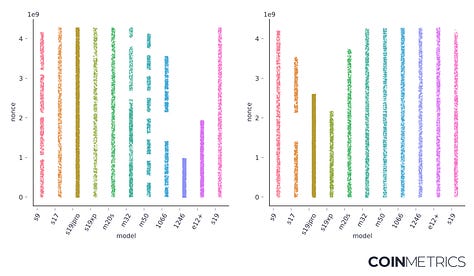

This issue is a follow-on topic from last week’s Bitcoin Nonce Analysis report. That report used a novel analysis of nonce data to infer the ASIC composition of the Bitcoin mining network. Nonces are the solution to a hash function used in mining, one of the key innovations that makes Bitcoin possible—Proof of Work. Here we’ll dive into some more details of these mathematical functions to give even more context to this cutting-edge report.

What is a hash function?

A hash function is a function that takes a sequence of bytes as input and, regardless of the length of that input, produces a fixed length sequence of bytes as an output. This output byte sequence is referred to as the hash of the original input sequence. But don’t get confused, often the function itself is referred to as a hash as well.

A common example of a hash function is SHA3-256. It returns a 256 bit hash, or one of 2256 possible outputs. Practically speaking, this hash is stored on a computer as a sequence of 256 0’s and 1’s. Hence, any piece of information on a computer, for example a file, also has a SHA3-256 representation that is 256 bits, or 32 bytes in length.

Properties of Hash Functions

While many functions qualify as hashes, good hashes exhibit four properties: deterministic, non-colliding, irreversibility, and uniformity. If a particular hash function exhibits these properties it can be very useful from a cryptographic perspective. Let’s explore each property below.

Deterministic

Deterministic means the function will return the same output given the same input. That is, there is no “randomness” in the function. This is helpful, because if a hash function is deterministic, one then knows that if they use the same input, the same hash value will always come out.

Concretely, for example SHA256(“coinmetrics”) will always result in this exact output:

3ace04d3a64b0be99967ca142c0dc46c841ece539238c36e9e37828b2aa404acYou can verify this here. Most common hash functions like SHA-256 are widely available and open-source tools.

Non-Colliding

Non-colliding means that no two inputs will produce the same hash. Thus, every input sequence has a unique hash representation that it produces and no other input can make that same hash. So, if two files produce the same hash, they must be the exact same file.

For example, this means that SHA256(“coinmetrics1”) will always be different from SHA256(“coinmetrics”).

Irreversibility

Irreversibly means that for any input sequence one can produce its hash, however, given a hash, one cannot reproduce the original input sequence. This is helpful because one can openly share the hash of some file without sharing any information that can be used to recreate the original file.

This means that if we shared the hash

3ace04d3a64b0be99967ca142c0dc46c841ece539238c36e9e37828b2aa404acwithout any information about its input, there would be no way to infer it was generated from “coinmetrics” without brute-force trial and error. But given “coinmetrics” we can easily verify it does indeed produce this hash result.

Uniformity

Uniformity means that the hashes produced for a given input file are “randomly” distributed throughout the space of all possible hashes. To put this simply, a small change to the input, maybe only one letter difference, will completely change the hash produced. This is helpful because even small changes in the original input file are easy to spot when looking at the hash, because that new hash is very different from the original hash.

Compare the results from hashing “coinmetrics” vs. “coinmetrics1” below—even the slightest change to the input drastically changes the hash function’s output.

SHA256(“coinmetrics”) =

3ace04d3a64b0be99967ca142c0dc46c841ece539238c36e9e37828b2aa404acSHA256(“coinmetrics1”) =

01858068b4f1fccba10f4a99fd4542a48361ea425aac406f308f10690c04e07d

Hashes and Blockchains

Hash functions, and the hashes they produce, are used extensively throughout the crypto-ecosystem. Perhaps the most fundamental use of hash functions is in the linking together of blocks into the blockchain itself. Let’s explore this concept a little deeper.

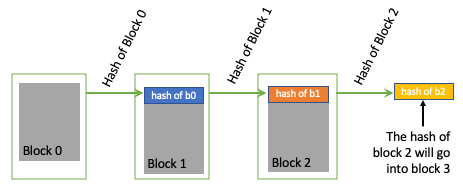

Examining Figure 1 below, a simplified blockchain is presented. Notice, each block contains within itself the hash of the previous block. This hash is an unique identifier for each block’s parent block. Recalling the properties of a hash function above, the blockchain is thus a data structure consisting of a unique set of blocks.

These blocks can be uniquely identified by following the linked hashes all the way from the head of the chain - the latest block to be produced - back to the genesis block - the first block produced. Due to non-collision and determinism, the chain of blocks can be traversed with complete accuracy down to a bit level.

Blockchains can thus be thought of as special cases of the broader class of linked-lists, with the unique property of 100% data validation. By simply comparing the hash of any block data, verification can be undertaken by any individual user. Further, the blockchain is incorruptible, because any change at any block along the chain would “cascade” forward down all the way to the head. Thus, one can know with certainty if the hash they have matches the hash of the head of the chain the entire blockchain is accurate down to the bit. This is truly a unique and powerful property for a data structure and is one of the key innovations of blockchain and crypto in general.

Figure 1: Simplified blockchain showing how hashes of each block both directly define the data structure as well as verify its content.

Hash Functions in the Bitcoin Mining Process

Hash functions are at the heart of the Bitcoin mining process. Fundamentally, what Bitcoin miners are doing is generating a very high number of unique hashes as quickly as possible in the hopes of finding one that works. Miners use a hash function (specifically SHA-256) to generate a hash value from something called the block header. That is, the header is the input sequence of bytes described above. The header contains information about the current block (transactions to be included, timestamp, etc.) as well as information pointing back to the previous history of the blockchain - a previous block’s hash. It also contains the nonce, or “number used once”, which is an integer value used to generate new unique hashes, as the rest of the information stays constant in the block header. As we explained, the nonce served as the key ingredient to our report The Signal & the Nonce to fingerprint different mining hardware.

The “work” element in Proof-of-Work mining directly refers to a hashing problem. This is explained in the Bitcoin whitepaper: “The proof-of-work involves scanning for a value that when hashed, such as with SHA-256, the hash begins with a number of zero bits.” The goal in Proof-of-Work is to find a hash that meets the criteria for a new block. A nice analogy to use is that of a large jigsaw puzzle (source). Jigsaw puzzles take a long time to piece together, but once complete, are easy to verify that they are in fact put together correctly. This is conceptually like the Bitcoin mining process.

What constitutes a “valid” or “solved” block hash has changed over time. This is because of an important network variable known as the difficulty parameter. As the name suggests, the higher the difficulty, the more computationally challenging it is to generate a winning hash. Think of this like moving from a 1,000 piece puzzle to a 10,000 piece puzzle. The purpose of the difficulty parameter is to regulate competition between miners by moving up or down every 2,016 blocks (~2 weeks) so that the network maintains a targeted 10-minute average time between blocks. The chart below shows this in action. At the time of writing, Bitcoin’s difficulty sits at an all-time high after several upward difficulty adjustments in the last year.

Source: Coin Metrics Network Data

Difficulty is enforced by mandating the structure of the resulting hash begin with a specific number of "0" bits. As the number of required 0s increases, the hashes become harder to find, hence requiring more work.

The higher difficulty is reflected in the “winning” block hashes over time. For example, we can look at the following block hashes for blocks in 2009, 2010, 2017, and today in 2023. You can see that the required number of leading zeros has increased over time, reflective of the higher difficulty.

Block 1,000 (2009): 00000000c937983704a73af28acdec37b049d214adbda81d7e2a3dd146f6ed09

Block 100,000 (2010): 000000000003ba27aa200b1cecaad478d2b00432346c3f1f3986da1afd33e506

Block 500,000 (2017): 00000000000000000024fb37364cbf81fd49cc2d51c09c75c35433c3a1945d04

Block 794,482 (2023): 00000000000000000001dae1b846b8e207fb56c87c4d8ba2033442a64b81f4d4

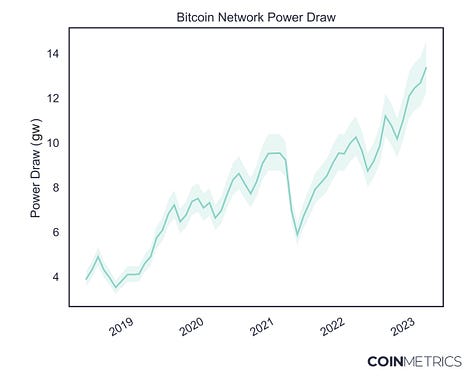

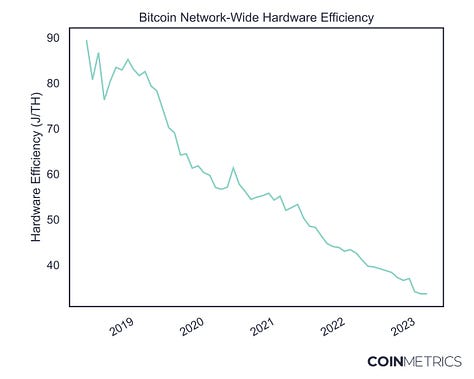

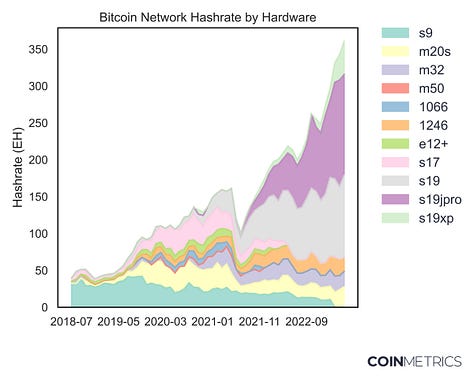

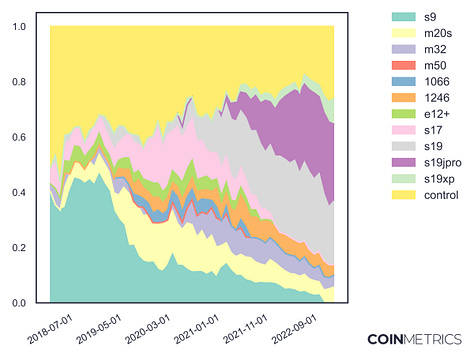

This is ultimately a reflection of more and more miners joining the network over time with better machines optimized to hash more quickly. This is shown by the network Hash Rate, a metric which is an estimate of the total aggregate rate of hashes on the network. Today, Bitcoin’s hash rate sits at around 350 EH/s (quintillion hashes per second).

Source: Coin Metrics Network Data

Bitcoin Mining: A Toy Model

A simplified model can help build intuition for this topic. Below, we’ve written a short Python script to simulate the mining process. Note this skips some nuance but hits on the major points. We can see the role of the hash function, the nonce, and the difficulty.

import hashlib

import time

def mine(block_number, transactions, previous_hash, difficulty):

# number of leading zeros required in the hash

prefix_zeros = '0' * difficulty

start = time.time()

hash_count = 0

for nonce in range(0, 2**32-1): # nonce space is a 32 bit unsigned int (between 0 and 4,294,967,295)

# create a candidate block by concatenating parameters

block = f'{block_number}{transactions}{previous_hash}{nonce}'.encode()

# hash the candidate block

new_hash = hashlib.sha256(block).hexdigest()

hash_count += 1

# check if the new hash has the required number of leading zeros

if new_hash.startswith(prefix_zeros):

elapsed_time = time.time()-start

print(f'Success! Hash is: {new_hash} and nonce value is: {nonce}, we did {hash_count:,} hashes in {elapsed_time:.3f} seconds, for a hashrate of {hash_count/elapsed_time:,.0f} hashes per second!')

return elapsed_time

raise ValueError('Failed to mine a new block.')Running on our local laptops, we can find a valid block with 6 leading zeros in a short amount of time (usually a few seconds to under a minute). But moving to 7 leading zeros, we see the average time jump considerably to find such a hash. Of course, if we were generating more hashes with a more powerful machine, we could lower these times considerably. This helps simulate some of the core concepts underpinning Proof-of-Work.

Try it out yourself!

Conclusion

While much more could be said about hash functions, hashes, and hashing within the crypto-ecosystem, we’ve covered the basics and outlined hashing’s role in the Bitcoin Mining process as well as its role in the blockchain data structure itself.

This issue is the second installment of the new “Foundations” series explaining technical topics related to crypto. Any feedback or thoughts are very welcome and can be submitted here.

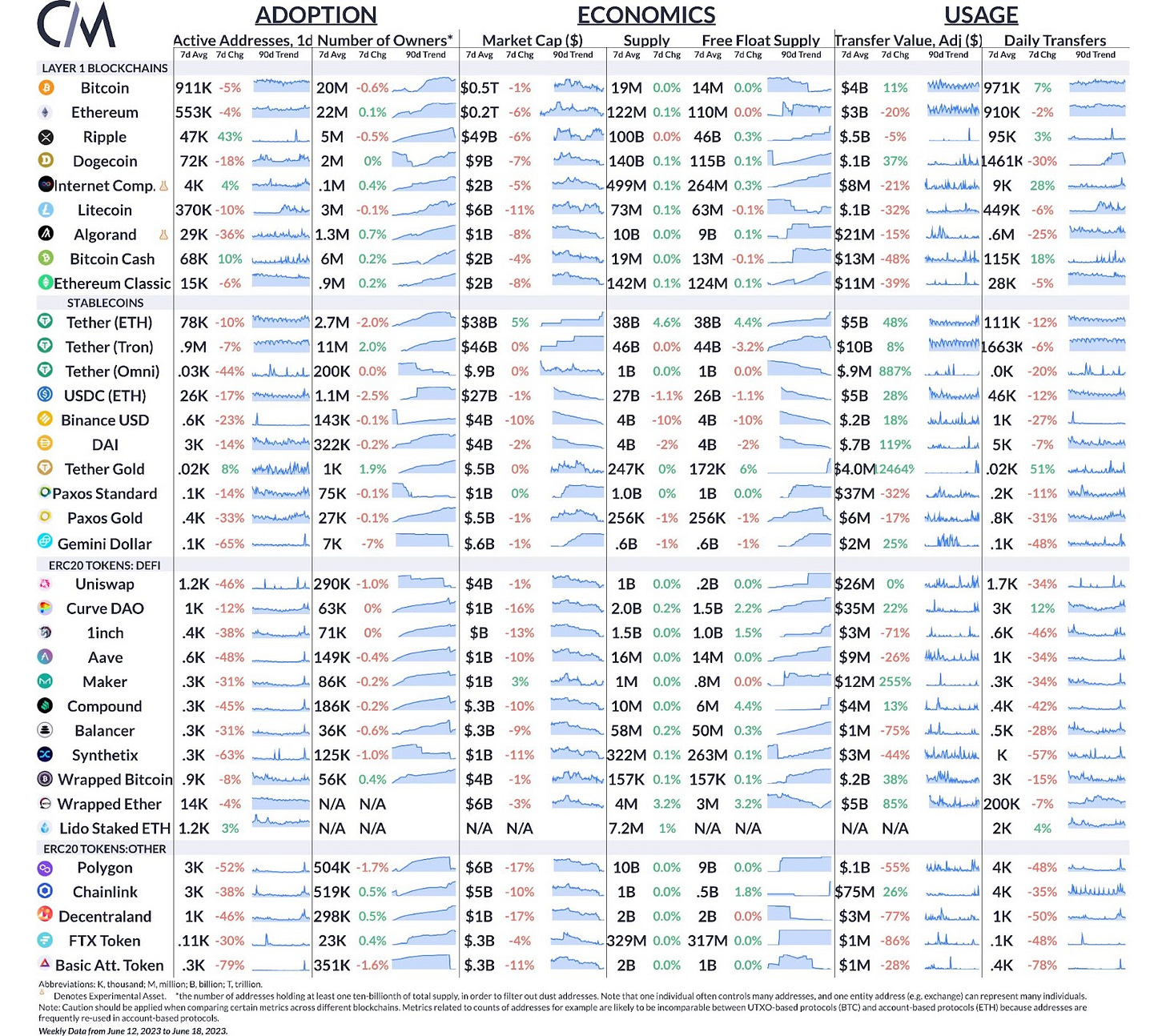

Network Data Insights

Summary Metrics

Source: Coin Metrics Network Data Pro

The market capitalization of stablecoin Tether (USDT) continues to grow, reaching $83B across Tron, Ethereum, and Omni. With 38B of USDT supply on Ethereum, this gives Tether a greater than 50% share of the market on ETH for the first time since March of 2021.

Coin Metrics Updates

This week’s updates from the Coin Metrics team:

In case you missed it, last week we released a sweeping new report fingerprinting Bitcoin ASICs to derive better insight into critical issues like Bitcoin’s energy consumption and E-waste. Check out The Signal & the Nonce here.

The Signal & the Nonce We also released a dashboard showcasing the new data from the report at https://labs.coinmetrics.io/

As always, if you have any feedback or requests please let us know here.

Subscribe and Past Issues

Coin Metrics’ State of the Network, is an unbiased, weekly view of the crypto market informed by our own network (on-chain) and market data.

If you'd like to get State of the Network in your inbox, please subscribe here. You can see previous issues of State of the Network here.