Coin Metrics' State of the Network: Issue 30

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Get the best data-driven crypto insights and analysis every week:

Weekly Feature

Ranking Crypto Assets by Auditability

by Antoine Le Calvez and the Coin Metrics Team

In Medieval times, landed estates’ accounts were read out loud to a person charged by the local ruler to ensure that their steward had not swindled them. As the primary role of this person was to listen (audire in latin), they became known as auditors.

A parallel can be drawn between the genesis of auditing and crypto asset nodes that do not take part in that asset’s consensus; they primarily serve to listen to the peer-to-peer network and validate that everything is unfolding according to the protocol’s specification: they are auditing the network.

Coin Metrics takes this approach one step further: as well as running nodes for most major crypto assets, we also extract raw blockchain data from them to rebuild the asset’s ledger independently. This allows us to compute many of our metrics (for example, realized capitalization) but also to more deeply analyze each asset.

Our version of auditing a crypto asset is being able to rebuild its ledger (the mapping of who owns what) independently, for any point in time, using data provided by the asset’s protocol implementation and, using this reconstructed ledger, verify that its supply matches what it should be according to the protocol’s specification.

In this feature, we’ll dig into how we audit crypto assets, what difficulties can be encountered during this exercise and what can be learned from it. Finally, we’ll attempt a ranking of assets along two different dimensions of auditability: node operation and ledger reconstruction. Note that those rankings are arbitrary and that they reflect our subjective experience of working with each asset.

Crypto Assets Auditability Dimensions

Node Operation

The first step to audit a crypto asset is to synchronize a node that understands its protocol. The node is software that implements the asset’s protocol, connects to the peer-to-peer network, and downloads and verifies the blockchain. Depending on the asset, hardware and time requirements vary. For some assets, there are different node variants to choose from, either because parallel implementations of the same protocol exist, or there are various configurations possible depending on the user’s needs.

In the case of an auditor, it’s better to use the configuration that will give access to the most data possible, sometimes referred to as an archive or full history node. Depending on what level of audit is needed (current or historical audit), a configuration that doesn’t store all historical data could suffice, for example, pruning mode in Bitcoin Core.

Synchronization

The first thing a crypto asset node does is synchronize itself with the current state of the network. Depending on the asset and configuration, this could involve downloading a current or recent snapshot (for example, downloading a recent Ethereum’s state trie using fast sync) or downloading the entire history of the block chain and replaying it in its entirety (like what Bitcoin does). While the former is much faster, the latter is better suited for auditing as it makes historical data available.

For some assets and node configuration, completing this process requires a lot of patience (and expensive hardware). As an example, synchronizing a full archive EOS node took more than one month and required a machine with terabytes of NVMe SSDs, some of the fastest storage available.

Finally, a handful of assets, most notably Ripple, require such huge amounts of storage (tens of TBs) that they are impractical to run and synchronize.

Normal Operation

Having a node synchronized with the rest of the network is only the first step of the audit process. The node also needs to stay synchronized in order to be able to audit the network on an ongoing basis. While this sounds easy to achieve, a lot of node software fails to stay synchronized and sometimes experiences catastrophic failures during normal operations.

An example would be that our EOS node needs to be shut down very carefully otherwise it risks corrupting its own database.

Code Audit

A major part of being able to audit an asset is being able to understand how it works. Since the implementation of each protocol lives in code, being able to read it is paramount to getting a deep understanding of the intricacies of each protocol. While some assets have deep, detailed specifications, they might differ ever so slightly from the actual implementation.

In that dimension, of the more than 35 unique nodes that Coin Metrics manages, one is unique: Binance Chain. It’s the only one whose source code is not available: only signed binaries are provided to would-be node maintainers.

Despite there being some documentation on Binance Chain’s protocol, it’s not detailed enough to be able to reconstruct its ledger using the data exported from the node.

Extracting Ledger Data

The last step before being able to reconstruct an asset’s ledger is to be able to extract the necessary data from the node. Few assets’ nodes offer the ability to directly obtain the latest (or historical) ledger; most of the time, it has to be rebuilt by replaying the asset’s history.

In order to do this, we need to be able to extract all the data required from the node. All nodes offer some form of API to access this data, with varying levels of user-friendliness, documentation, and completeness.

A key to easy auditability for an asset is to have as few ways as possible to credit or debit accounts. For example, Bitcoin only has 1 way to credit native units (the mining of an unspent output) and one way to debit native units (spending a previously unspent output). The more distinct things there are to track, the harder it gets. The more ways there are to credit/debit native units, the more likely that data for some is not easily accessible (an example would be some fees charged by the Binance Chain DEX).

Node Operation Ranking

We ranked full nodes in several tiers (A, B, C, and F) depending on their ease of synchronization, update, and maintenance. Here is our ranking for the top 10 assets by market cap (Coin Metrics doesn’t operate Ripple or Stellar nodes, but relies on the APIs provided by both Ripple and the Stellar Foundation).

Since historical ledger auditing for Ethereum requires a node with tracing and they take a long time to synchronize, it gets a B.

Omni gets a B as, even though it’s a modified Bitcoin Core and is therefore easy to run and sync, it has many different ways to credit and debit native units, each accessible through its own API endpoint requiring some effort to understand and put together.

Despite having a very clean accounting model for an asset of its complexity, EOS gets an F due to the complexity of extracting all the necessary data to run a complete audit. An archive node running with an extra plugin is required, documentation for which is scarce. Finally, the amount of data to sift through in order to get credits and debits of EOS is very large which makes it impractical.

Binance Chain gets an F for two linked reasons: it has a very complex fee schedule for its DEX and it’s closed-source which makes reverse engineering this schedule very hard.

Ledger Reconstruction

Once the node is synchronized, running correctly and its data exported, the task of rebuilding its ledger can begin.

The way this is accomplished depends on the asset’s accounting model: UTXO-based (like Bitcoin and its derivatives) or account-based (Ethereum and many others). The ledger for UTXO based chains’ consists of a set of unspent transaction outputs (UTXO). Therefore, rebuilding the asset’s ledger consists of tracking which transaction outputs are unspent. For account based chains, the ledger is closer to a mapping of accounts to their balance. In order to rebuild it, auditors have to keep track of credits and debits for each account.

UTXO Sets

Tracking unspent outputs is done by replaying the block chain: each block creates new outputs and spends old ones. After having replayed the whole chain, the outputs remaining unspent make up the asset’s ledger. Summing up their value gives the asset’s supply.

As straightforward as it seems, there are still some nuances to keep in mind. We detailed some of Bitcoin’s supply idiosyncracies in a recent installment of this newsletter. For example, some special outputs (OP_RETURN) are not counted towards the supply; Bitcoin’s genesis block’s output doesn’t count either.

Account Ledgers

For account-based chains like Ethereum, we have to track credits and debits for each account on the chain. Given the complexity of some chains driven by the existence of smart contracts, this can get complicated very quickly.

Another difference between UTXO and account-based protocols is that transactions in the former are more explicit about how they affect the ledger:

A UTXO transaction consists of two parts: which previously unspent outputs it spends and what new outputs it creates. UTXO transactions describe how they are going to change the asset’s ledger. On all UTXO protocols, only valid transactions are included in valid blocks. There cannot be partially applied UTXO transactions.

Account-based transactions, especially smart contract invocations, only describe the intent of the user, not its effects on the ledger. To be able to recover their impact on the ledger, nodes often need to be run with what is often called “tracing”. Tracing consists of recording exactly what each transaction’s impact on the ledger was. Non-tracing nodes just apply transactions without making detailed information available on a per-transaction basis. Furthermore, transactions can be included in a block without being completely executed.

For some assets, there are additional factors listed below to take into account.

Implicit Block Rewards

Most protocols include a reward for whoever (miner or staker) added a new block to the chain. The reward’s amount is the implementation of the asset’s monetary policy as this is how most assets generate new coins. Therefore, tracking this is essential to determine an asset’s supply.

In most UTXO assets, this amount is visible in each block, as the first transaction of every block encodes this reward being given to the miner. However, this is not always the case for account-based ones, most notably Ethereum, where blocks just encode which account should get the reward. The exercise of determining the reward’s amount is left to nodes and auditors.

As Ethereum block reward changed twice so far (5 ETH→3 ETH→2 ETH), auditors and nodes have to keep track at which blocks those changes happened.

Implicit Ledger Edits

While the block reward being implicit is only a minor inconvenience, there are other times where an asset’s ledger can change without those changes being made explicit by the transaction or blocks.

For example, following the DAO attack, Ethereum experienced a hard fork to return funds withdrawn from the DAO to another address not controlled by the person behind the unexpected DAO withdrawals. Those changes to the ledger are implemented in the code run by the nodes, not in a transaction nor in a block. Unfortunately for auditors, neither the block raw data nor the tracing data indicate that those changes occurred. The only way to capture those credits and debits is to find the hardcoded list of affected addresses and emulate what edits the code ran over the ledger.

This type of software-only changes to the ledger also recently happened with Tezos. In the making of the Babylon hard fork, someone realized that thousands of accounts would have to be recreated by users in order to access some of their funds: an operation that costs 0.257 XTZ. In order to avoid having thousands of users pay this fee, the hard fork was changed to credit affected accounts with a tiny amount of XTZ to “recreate” them at a lesser cost. Once again, auditors were out of luck as this subtle change was not documented anywhere.

A final example of how implicit ledger edits make auditing assets more complicated lies with ERC-20 tokens. ERC-20 is a standard interface for Ethereum smart contracts. It lists a few methods and events they should implement to maximize compatibility with existing wallet software and explorers. In practice, ERC-20 is just a standard and lacks strong guidance on the semantics of its events. Developers are free to stray from it, leaving auditors like Coin Metrics the hard task of piecing together the asset’s full transactional history. For example, token generation and burn events are often recorded using token-specific methods (if recorded at all).

Ledger Reconstruction Ranking

We’ve ranked each of the top 10 assets in several tiers (A, B, C, and F) depending on the ease of rebuilding their ledger for any point in time:

Ripple and Stellar are not graded as we do not reconstruct their ledger completely independently as we rely on APIs provided by third parties.

Bitcoin and its derivatives (Bitcoin Cash, Litecoin, BSV) receive an A as tracking their UTXO set is a simple task.

The Omni protocol, used by Tether to operate on the Bitcoin blockchain, receives a B because it has many different ways to move native units which makes it harder to track.

EOS also receives a B because its sheer scale (tens of millions of transfers per day) makes it unwieldy to audit.

For Ethereum, the current state of the tools we use don’t allow a full reconstruction of the ledger only using the data exposed by tracing, the changes made in the DAO hard fork have to be manually implemented. It therefore receives a C.

Finally, Binance Chain received an F because we could not rebuild Binance Chain’s ledger using our node’s data, due to the complexity of its DEX and the absence of source code to look up the details of its implementation.

Validating the Supply

Once the historical supply of an asset can be computed, it still has to be validated against what it should be to ensure it’s correct. This category doesn’t have a ranking as it’s binary: either we can validate the supply or we can’t due to being unable to reconstruct its ledger. There’s been no case of an asset for which we couldn’t determine what the expected supply should be.

A few assets’ nodes let users query what the actual supply is (most notably Bitcoin and its derivatives) which makes this task easy.

Example of fetching Bitcoin’s supply

For the other assets, most of the time, they have a straightforward issuance (or none at all). Given the formula that gives the expected supply at a given height and the supply we found rebuilding the ledger, we can verify whether there’s been any unexpected inflation. It’s possible to find a lower supply than the formula’s due to users or entities burning funds.

Some assets, due to their use of privacy features, sacrifice supply visibility for transactional privacy. One interesting example is Zcash which has the particularity of having both a visible part of its supply (so-called transparent supply) and a private part (so-called shielded supply). Auditors have perfect visibility into the makeup of the transparent ledger but can only have an estimation of the size of the private part. Movements in and out of the private supply can be tallied to estimate its size, but if there’s an inflation-causing bug happening inside fully private transactions, it is undetectable by auditors.

Conclusion

It’s important to note that a lot of the issues we encounter in auditing crypto assets lie with the nodes and tooling available to users, not with the protocol themselves. We hope that over time, they will improve to make auditing assets easier, and we are already starting to see this today. Coin Metrics may therefore revisit this exercise in the future.

While this exercise of validating an asset’s supply independently may seem futile, it nonetheless led to several discoveries of hidden inflation.

Coin Metrics detected that Bitcoin Private supply had anomalies using these auditing techniques:

Stellar suffered an inflation bug visible through supply auditing that was later remediated by the Stellar Development Foundation burning some of its own supply. As a further argument to why this process matters, the total supply as reported by the Stellar blocks headers diverged from the actual supply of XLM obtained by summing up all the account’s balances.

These two examples once again highlight the relevance of one of the industry’s adages: do not trust, verify.

Network Data Insights

Summary Metrics

The major crypto assets continued to downslide over the past week. BTC and ETH market cap both fell by over 2.6% and realized cap dropped 0.2% and 0.6%, respectively.

ETH active addresses count, however, grew 21.3% week over week. This large increase is potentially related to Ethereum’s recent Istanbul hard fork. ETH transfer and transaction count were also up over the past week, despite a large decrease in transfer value.

XRP transactions, however, continued to decline after a large surge in recent weeks. XRP active addresses dropped by over 13%, far more than the other four assets in our sample.

Network Highlights

Bitcoin SV (BSV) transaction count hit new yearly highs this past week. However, as we reported back in SOTN Issue 8, a majority of BSV transactions are being used for data storage, and do not involve monetary transfers. At one point, over 90% of all BSV transactions were being initiated by WeatherSV, an app that records daily weather data onto the blockchain for a small fee. There is now another BSV app that is generating a large number of transactions: Preev, which allows users to write once-per-minute price updates for BTC-USD onto the BSV blockchain ledger.

The number of addresses with small balances of Tezos (XTZ) has been growing since early November. The following chart shows XTZ addresses with balance greater than X, where X ranges from 0.1 XTZ to 1K XTZ.

On November 7th, Coinbase introduced Tezos staking, and added Tezos to Coinbase Earn, which allows users to earn up to $6 worth of XTZ by completing some lessons to learn how it works. There were a little over 82,000 addresses with at least 0.1 XTZ (worth about $0.16 at current prices) on November 6th. As of December 15th, there are over 107,000 addresses with at least 0.1 XTZ.

Market Data Insights

Crypto markets continued with a steady but moderate decline in prices over the past week, with a few noticeable exceptions. After consistently underperforming other major assets for the majority of this year, ZCash has achieved two consecutive weeks of positive price growth.

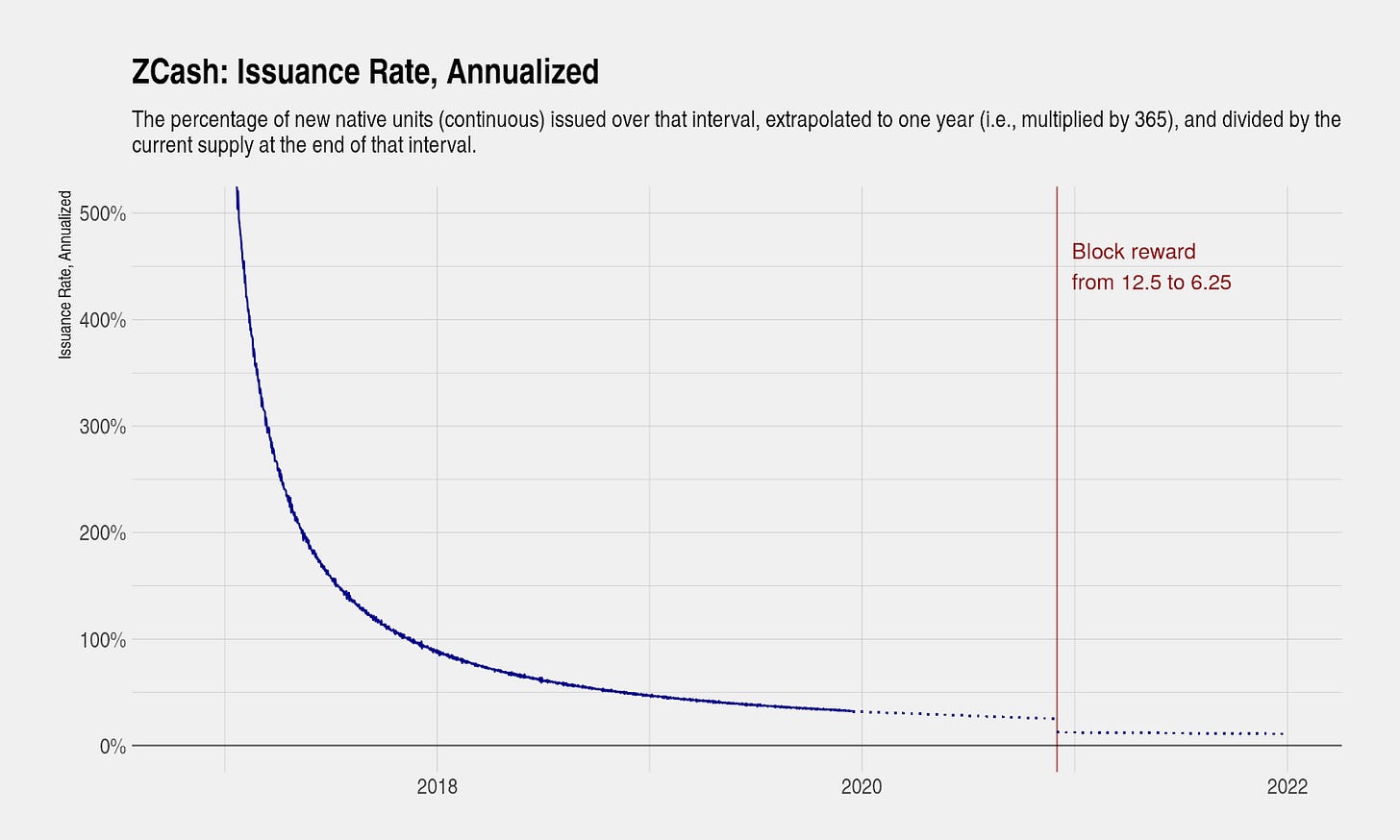

ZCash has underperformed other major assets this year in part because of its high issuance rate. As a relatively young proof-of-work asset modeled off of Bitcoin’s issuance schedule, ZCash was launched in October 2016 with no premine and a block reward of 12.5 ZEC per block. ZCash has yet to experience a block reward halving and its annualized issuance rate is relatively high compared to other proof-of-work assets.

Notably, ZCash annualized issuance rate has been declining rapidly as the constant block reward represents a smaller percentage of its total supply. Over the course of 2019, the annualized issuance rate has declined from 47% to 32%. By late 2020, the annualized issuance rate will further decline to 25% just prior to the block reward halving and will then decline to 12.5% immediately after the halving. These reductions in miner-led selling pressure should be broadly supportive to prices assuming that demand for ZCash remains constant.

Other notable performers this week include ChainLink (+1%), Tezos (+5%), and Cosmos (+15%). All three assets are extending significant gains over the course of this year.

CM Bletchley Indexes (CMBI) Insights

As the year comes to a close it is time to reflect back on where we have come from a year ago to put the current market performance into context. Despite the recent weakness in the market, crypto asset performance has been relatively strong over 2019 after an abysmal 2018. With renewed confidence in the market, it seems most of the attention has gone into larger assets, with Bitcoin close to finishing the year up over 80%, the Bletchley 10 (large cap) returning 52% over the year, the Bletchley 20 (mid cap) returning 28% and the Bletchley 40 (small cap) falling 40%.

However, after a soft week for crypto asset markets that saw prices dwindle across the board, all Bletchley Indexes finished the week ~5% down. There was very little differentiation in performance between small, mid and large-cap assets as is evidenced by the below charts, demonstrating very little variance in weekly returns.

Coin Metrics Updates

This week’s updates from the Coin Metrics team:

Coin Metrics is hiring! We have 6 roles posted including Blockchain Data Engineer and Data Quality and Operations Lead. Please check out our Careers page to view the openings.

As always, if you have any feedback or requests, don’t hesitate to reach out at info@coinmetrics.io.

Subscribe and Past Issues

Coin Metrics’ State of the Network, is an unbiased, weekly view of the crypto market informed by our own network (on-chain) and market data.

If you'd like to get State of the Network in your inbox, please subscribe here. You can see previous issues of State of the Network here.

Check out the Coin Metrics Blog for more in depth research and analysis.