Coin Metrics' State of the Network: Issue 45

Tuesday, April 7th, 2020

Get the best data-driven crypto insights and analysis every week:

The Signal and the Nonce Redux: From S9s to S17s

By Karim Helmy and the Coin Metrics Team

As Bitcoin enters its next halving, the network is experiencing several simultaneous transitions. In addition to the severe change in mining economics being caused by the reward adjustment, Bitmain’s Antminer S17 is in the process of replacing the longstanding S9 line of miners as the dominant mining hardware on the network. The first rig in the S9 line, the eponymous Antminer S9, was released by Bitmain in 2016 and quickly became the most popular SHA-256 miner; as a result, the network has not experienced such a shift in years.

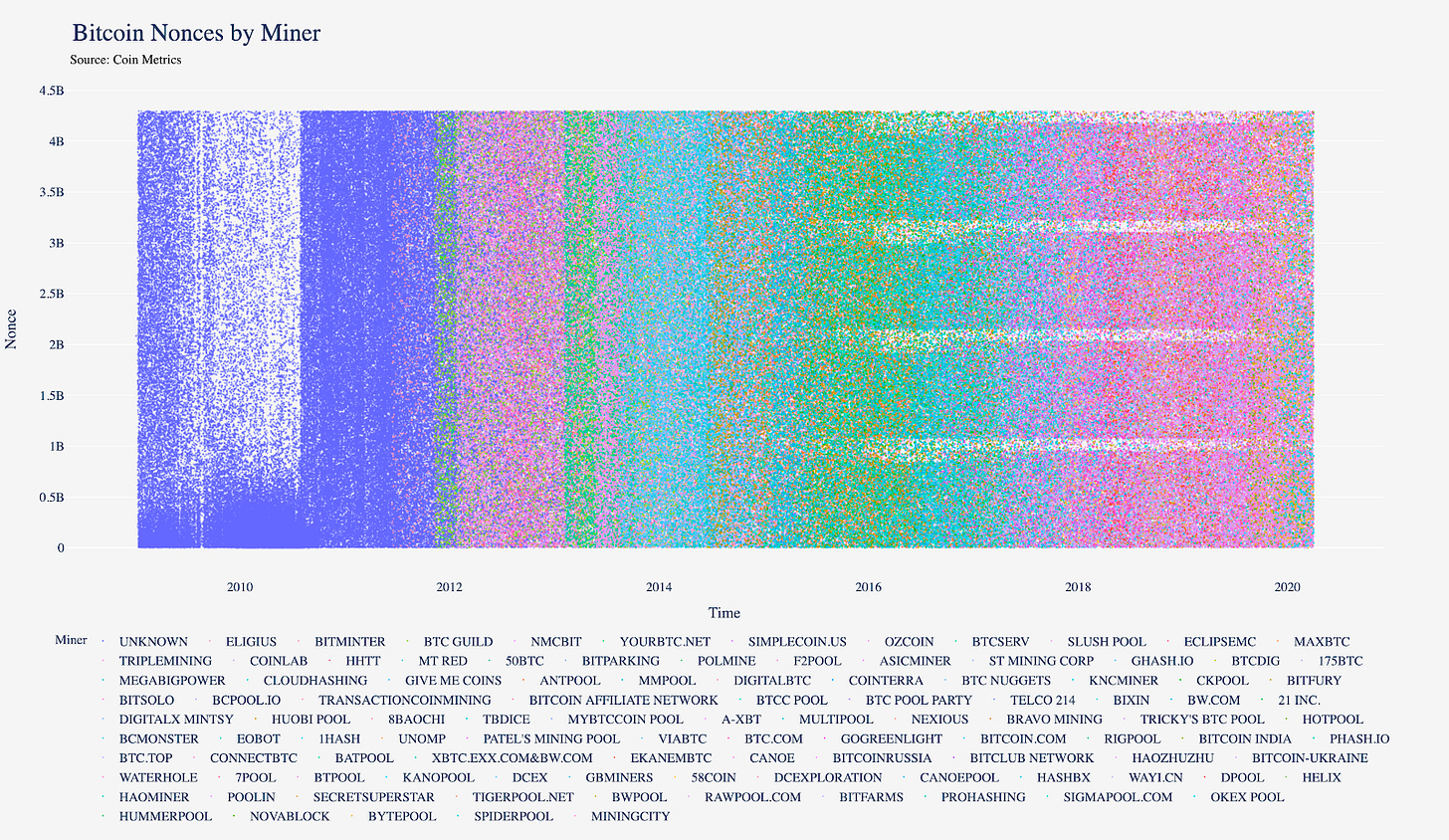

Due to a lack of publicly available data about the types of mining hardware used by individual miners, it can be difficult to measure the rate at which this transition is occurring. One unexpected source does shed some light on mining hardware trends, though: the network’s nonce distribution. The arrangement of these arbitrary numbers, included by miners as part of each block’s hash, hints at how mining hardware usage has shifted over the years.

In a previous issue of state of the network, we investigated how nonce distributions patterns can be used to spot the rise of ASICs. In this issue, we’ll dig further into the peculiarities of Bitcoin’s nonce distribution and the sources behind the distribution’s striations to investigate the recent shifts in mining hardware. We’ll then break down this data by mining pool, which allows for more granular insight into the hardware used by specific pools.

Golden Marbles - Understanding The Mining Process

Mining is a critical part of Bitcoin’s security model and arguably the most important improvement on previous attempts at creating digital money. Although the implications of mining are quite complex, the concept behind it is relatively simple to understand.

From the perspective of a miner, mining a block resembles repeatedly selecting marbles from a bag without replacement. In this analogy, the number of marbles is very large, with a large proportion of blue marbles and a small proportion of gold marbles. Miners receive a payout on pulling a gold marble from the bag.

Explained in more technical terms, Bitcoin miners compete to find a golden nonce that, when appended to the header of a proposed block, hashes to below a certain value determined by the network’s difficulty parameter. Miners search for this nonce, or arbitrary number, that can only be used once, by guessing values and checking if the resulting hash is below some threshold. The first miner to find such a value for a valid block and broadcast it to the network receives the right to choose and order the transactions within the block, a necessary step for these transactions to be eventually considered valid.

In return, the miner also receives a payout from the block reward and fees from any transactions included in the block, both of which are received in a special coinbase transaction. Provided that the purported properties of the SHA-256 hash function hold, the distribution of golden nonces for any given block is random and a golden nonce cannot be found except through brute-force computation.

Because a reference to the coinbase transaction is included in the block header, each mining entity is sampling from a different distribution. In other words, each entity is pulling marbles from a different bag, where bags contain the same number of marbles and, in expectation, the same ratio of blue and gold marbles.

The proportion of golden marbles is determined by the network’s difficulty parameter, and is fixed for the relevant period. The difficulty parameter is automatically adjusted by the network. Today, due to a high block difficulty and random variance, there are often no golden nonces for a specific block header. In other words, there are some bags that contain no golden marbles.

Miners who exhaust the nonce space of a proposed block typically increment the block’s timestamp to generate a new set of nonces. That is to say, when a miner runs out of marbles, they grab a new, full bag. If the timestamp has reached the point where further adjustment would render it invalid, the miner must adjust the set of transactions included in the block. Analogously, if a miner runs out of bags in their room, they need to grab some more from another room, which is time-intensive.

To increase their probability of finding a golden nonce in a fixed period of time, miners can parallelize their computations, which is analogous to pulling marbles by the handful rather than one at a time. Nonce-finding can be parallelized by using hardware suited to the task, in particular graphical processing units (GPUs) and specialized chips known as ASICs. ASICs are much more efficient at parallelization than any alternative, and today account for virtually all of the network’s computational power, or hashpower.

In another form of parallelization, several miners coordinate their nonce-finding and agree to split any payouts. This strategy reduces both the size and variance of a miner’s payouts, and does not change expected long-run revenue. Groups of miners acting in this way are known as pools. The operator of a pool typically charges a fee, which individual miners accept in exchange for a reduction in income volatility.

Bitcoin’s Nonce Distribution

Every two weeks, Bitcoin’s difficulty parameter is adjusted so that a new block would be produced every ten minutes on average if the amount of computation performed on the network were to remain constant. This feature ensures the network will continue to operate in spite of potentially large changes in hashpower. In a sufficiently competitive mining market dominated by miners who are computing values in parallel, then, we would expect the plot of golden nonces over time to look like evenly distributed static. Surprisingly, it doesn’t.

The non-random distribution near the left-hand side of the plot can be attributed to mining by iteratively testing values starting at 0. If a miner is mining without parallelization on a CPU and as an individual, and therefore has no possibility of running collisions with other members of their pool, this strategy is as valid as any other, since the nonce distribution for each new block is independent. The disappearance of this pattern coincides with the introduction of GPU miners, which parallelize computation.

Near the right-hand side of the plot, there is a striated pattern of regions with very few nonces. To our knowledge, this anomaly was first noticed by Twitter user @100TrillionUSD in January of 2019. The same plot, with the striated region labeled, is shown below.

The bizarre pattern was the subject of a BitMEX research piece shortly after, which speculated that the anomaly was the result of a quirk in an implementation of AsicBoost, a controversial mining optimization technique.

There are two variants of AsicBoost: covert AsicBoost, which cannot be definitively observed on-chain, and overt AsicBoost, which can be. The BitMEX research team discusses both variants, but is particularly interested in the effect of covert AsicBoost, the use of which was made practically impossible for non-empty blocks with the activation of SegWit in August of 2017. The researchers could not confirm their hypothesis.

The streaked pattern indicates that miners are systematically undersampling certain ranges of possible nonces. By excluding certain ranges from sampling, miners are effectively partitioning their marbles into a small number of different bags and refusing to pull from certain bags. In expectation, the color ratio of each bag is equal, so miners do not change the probability of selecting a golden marble on the first try by doing this. Because the number of marbles in each bag is very large, the reduction in effectiveness caused by adopting this strategy when sampling repeatedly is small. This strategy does, however, increase the frequency with which miners must grab a new bag of marbles, which can be expensive. Since each mining entity is sampling from their own distribution, other pools cannot use knowledge of an entity’s adoption of this technique to their advantage by strategically sampling.

In October of 2019, State of the Network Issue 23 looked at Bitcoin’s nonce distribution in depth and noted the streaked pattern. Since then, the striated pattern has faded, and the nonces of recently-mined blocks appear to be more randomly distributed.

The anomalies in the nonce distribution do not appear to be directly related to AsicBoost. Covert AsicBoost became unusable in 2017, and the first firmware update enabling overt AsicBoost was publicly released in October of 2018, but the striations are clearly visible between these two dates. Additionally, while overt AsicBoost usage remains high, the patterns are no longer visible in blocks mined either with or without overt AsicBoost.

Instead, the patterns in the nonce distribution may be caused by the manner in which Bitmain’s Antminer S7 and S9 families of miners sample nonces. This artifact is likely an unintended side-effect of optimization, and is ultimately harmless to both the miner and the network.

The S7 and S9 lines contain several related models using the BM1385 and BM1387 chips, respectively. The period in which each line of miners was dominant on the network corresponds to a distinct phase in the patterning of Bitcoin’s nonce distribution.

When observing all nonce values on the network, the streaked pattern first becomes clear in late 2015, coinciding with the release of the S7 in late August of that year and the fulfillment of orders in late September.

The Antminer S9 was released in late May of 2016, with the purchasers of the first batch receiving their orders in mid-June of that year. Shortly afterward, the streaks become more narrow in concurrence with supersession of the S7 by the S9 as the dominant miner on the network in late 2016.

The pattern’s recent breakdown coincides with the transition from the S9 to the Antminer S17 as the dominant miner on the network. While the S17 was released in April of 2019, the use of S9s on the network has until recently remained common as they have continued to be economical to operate.

Pooled Analysis

Stratifying the dataset by each block’s miner allows for a more fine-grained view of the nonce distribution. Identifying the miner of a block is relatively straightforward but carries several caveats.

The miner of a block is typically identified through a tag left in the block’s coinbase data field. These identifiers are voluntary and falsifiable: miners are not required to leave a message, and may choose to leave another pool’s tag in place of their own. In certain situations, these misleading behaviors may even be incentivized, so the shortcomings of this approach should be recognized. This technique is the industry standard, however, and while many miners choose not to leave an identifier, we have no reason to believe that falsification is occurring on a significant scale.

The miner of a block is labeled according to their most recent identifiable block mined. This provides robustness against anomalies like hashpower voting, in which the coinbase data is used to signal support for a fork rather than to identify the miner.

Mining entities are also identified through reuse of a known payout address. This approach requires pools to reuse addresses, and is sensitive to the initial seed set of known addresses. For our purposes, this approach is used to supplement tagging based on the coinbase data in order to provide coverage for miners who do not leave a consistent tag.

Once we have categorized blocks by miner, we can incorporate this information into our plot of Bitcoin’s nonce distribution.

We can also take a look at the nonce distribution of individual pools. Even at this level, the anomalous patterns remain visible. Consider the plot below, which shows the blocks mined by Antpool and BTC.com, both of which are owned by BitMain, as well as ViaBTC, in which BitMain is an investor.

The streaked patterns are significantly clearer in the nonce distributions of Bitmain-affiliated pools than in that of the network as a whole. This indicates a higher proportion of S7s and S9s in these pools during the relevant period, which is to be expected given the pools’ association with the manufacturer of these miners.

The proportion of blocks mined by unknown entities shows a large drop-off in 2015. This is a result of the block size wars, during which many previously anonymous miners began to identify themselves on-chain in order to signal support or opposition to a block size increase. Today, the vast majority of miners by hashpower are identifiable. The striated patterns are faintly visible in the nonces of blocks mined by unknown miners, as is their gradual dissolution.

Conclusion

The Antminer S9 has until recently been the most-used miner on the Bitcoin network since its release in 2016. Despite the release of the S17 last year, the S9 remained economical to operate for a period, but the miner is being phased out in light of increasing hash rate and changing market conditions. The shift in dominance from the S9 to the S17 that is currently taking place in anticipation of the halving has not been properly considered in many analysts’ assessments of the network.

In parallel with miners’ transition from predominantly using the S9 to the S17, the streaked patterns that were formerly the defining feature of Bitcoin’s nonce distribution have dissolved. The source of these mysterious streaks, which appear in a space that should look random, has been the subject of significant speculation. The timing of the streaks’ visibility lends credence to the theory that these lines were an artifact of the hardware used to mine on the network, in particular the S9 and the S7 that preceded it.

Nonce data allows us to gauge the scale and pace of this shift, using only public information, in a manner that would otherwise be impossible. By taking advantage of the artifacts left by the S9 in the sampling of nonces, we may be able to estimate the proportion of these miners on the network. The segregation of this data by pool gives unique information on the efficiency of miners’ operations, to be covered in a future report. This issue paves the way for a formal assessment of this type.

Network Data Insights

Summary Metrics

Source: Coin Metrics Network Data Pro

Bitcoin (BTC) mining showed healthy signs of recovery this past week with estimated hash rate increasing by 7.3%. Inefficient miners have likely already started to capitulate and are being replaced by more efficient miners, which is positive for the long-term health of the network. For more on miner economics and the implications of the recent difficulty decrease, see State of The Network Issue 44 - Understanding Miner Economics From First Principles.

BTC active addresses also showed positive signs of recovery this week, growing by 6.3%. But Ethereum (ETH) active addresses went in the opposite direction, dropping by 13.4% week-over-week. ETH daily active addresses peaked at 537K on March 21st, the highest daily total since May, 2018. However, since then they have been declining - ETH had 310K daily active addresses on April 5th.

Network Highlights

The number of addresses holding relatively small amounts of BTC has been increasing since the March 12th crash.

The number of addresses holding between one billionth (1/1B) and one hundred millionth (1/100M) of the total BTC supply (i.e. between 0.000000001% and 0.00000001% of total supply) has increased about 6% over the last 90 days. Similarly, the number of addresses holding between one hundred millionth (1/100M) and one ten millionth (1/10M) of total supply increased about 4%.

Both had a noticeable increase in growth rate beginning around March 12th. This could signal that adoption is growing, as new users start acquiring relatively small amounts of BTC.

Source: Coin Metrics Network Data Pro

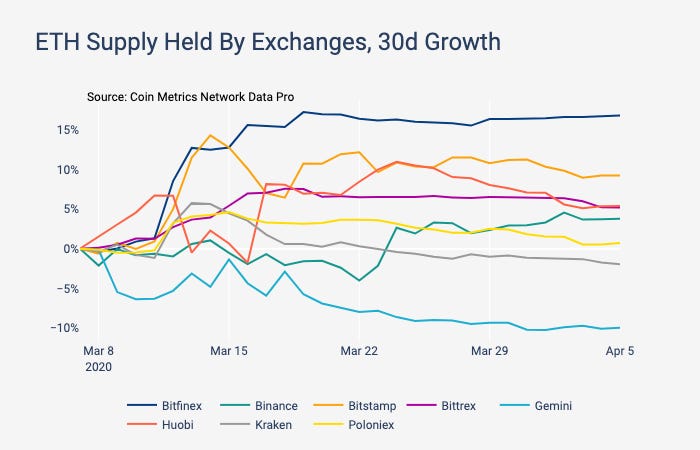

The amount of ETH held by the exchanges in our coverage (listed below) has grown over the last 30 days, while the amount of BTC held by exchanges has decreased.

ETH has increased by about 5%, while the amount of BTC held on exchanges has decreased by about 3%. The drop in BTC is largely due to the rapid decrease in supply held by BitMEX, as covered in the Network Highlights section of State of the Network Issue 44.

The below chart shows the 30 day growth for the total supply held on the following exchanges: Bitfinex, Binance, Bitstamp, Bittrex, Gemini, Huobi, Kraken, BitMEX, and Poloniex.

Source: Coin Metrics Network Data Pro

Bitfinex has had the largest increase in ETH supplies out of all of the exchanges in our coverage. The amount of ETH held by Bitfinex has increased by about 17% over the last 30 days, while no other exchange has had more than a 10% increase.

Source: Coin Metrics Network Data Pro

Market Data Insights

Markets are up sharply over the past week and are beginning to recover losses sustained on March 12. Our previous research finds that this sell-off was driven by short-term holders and reinforced by the BitMEX liquidation spiral. A broad consensus is forming that this sell-off, mirroring the sell-off seen in traditional markets, was at least in part due to technical dislocations in the market. Sentiment among retail investors appears to be unaffected as evidenced by increased user activity from Coinbase.

Source: Coin Metrics Reference Rates

The “risk-on asset” versus “safe haven asset” debate continues over Bitcoin. Some market participants have observed that Bitcoin’s safe haven narrative has been damaged over the past month which negatively impacts institutional investors’ appetite for entering the space.

A closer examination of Bitcoin and gold provides some evidence that the narrative is intact and could be stronger than ever. While Bitcoin did sell off aggressively in concert with equity markets, gold did too due to forced liquidations that happened in nearly every financial market. Since then, both Bitcoin and gold have recovered some of their losses.

Source: Coin Metrics Reference Rates

Bitcoin’s correlation with gold, measured over the past 30 days, is now at all time highs. Unprecedented monetary policy and fiscal stimulus from nearly every country in the world is forming the base for a credible narrative of increased risk of severe financial imbalances and the potential for long-term increases in inflation. Ultimately, these fears never materialized during the 2008 financial crisis, but conditions are ripe for these fears to resurface again.

Source: Coin Metrics Reference Rates

CM Bletchley Indexes (CMBI) Insights

CMBI and Bletchley Indexes all had a great week with ~15% increases across the board. The Bletchley 40, small-cap assets, performed the best of the market cap weighted indexes through the week, returning 16.9%. Interestingly the lower weighted assets within the Bletchley 40 were the top performers, demonstrated by the large returns of the Bletchley 40 Even and the Bletchley Total Even Indexes. For reference, the even indexes weigh all constituents equally, giving more weight to the smallest cap assets within the index.

The relatively low returns of all CMBI and market cap weighted indexes against BTC further demonstrates the uniformity of the week’s performance across the asset class.

Despite the strong performance of cryptoassets this week, monthly returns were still down significantly through March, with all CMBI single asset and Bletchley market cap weighted indexes down over 20%. The CMBI Ethereum index was the worst performer through March, falling 40.5% from $224.25 to close the month at $133.39.

Coin Metrics Updates

This week’s updates from the Coin Metrics team:

Coin Metrics is hiring! Please check out our Careers page to view the openings.

As always, if you have any feedback or requests, don’t hesitate to reach out at info@coinmetrics.io.

Subscribe and Past Issues

Coin Metrics’ State of the Network, is an unbiased, weekly view of the crypto market informed by our own network (on-chain) and market data.

If you'd like to get State of the Network in your inbox, please subscribe here. You can see previous issues of State of the Network here.

Check out the Coin Metrics Blog for more in depth research and analysis.